Currently, there are at least five court applications required to comply with the processes in an examinership. Each time, tests that are set out in the Companies Act 2014 must be satisfied to the court’s evidentiary standard.

This involves solicitors (and usually barristers) – and very much adds to the costs associated with getting court protection and, thereafter, the examinership process.

These court applications prompted an analysis of examinership – from preparing for the initial application for court protection (including the independent expert’s report and consequent petition/statement of facts), to the examinership process itself.

Countless applications taking days to prepare (incurring significant costs on behalf of examiners) are granted as a matter of course, adding not a whit to the survival of the company, and making no difference, save for satisfying obligations in the act.

The exit from examinership is usually clear to an experienced insolvency practitioner from the outset of the instruction. While the independent expert will identify the most obvious elements needed (I have never come across a case where investment, and a compromise of the balance outstanding to creditors are not two issues required), sometimes achieving certainty around rescheduling bank liabilities, or repudiating onerous contracts, are required to enable the examiner to certify to the court that the company has a reasonable prospect of survival as a going concern.

Despite its quirks, in its essence, the examinership process is straightforward. This being so, why is it so procedurally complicated and, as a result, expensive? Put another way, do the complications add to the process – and if not, why are they there?

Post pandemic

Small and medium enterprises (SME) promoters have had a torrid time in the past 12 years. Having recovered from the banking collapse in the late 2000s and the consequent absence of capital, they have been dealt another huge blow with COVID-19 mandated closures.

While there is a school of thought that a restructure is a charter for improper director conduct, this is absolutely not the case, and so the moral hazard argument against allowing a second chance does not stand up to scrutiny.

I have seen the stress etched into business owners’ faces, in the teeth of losing everything, including (typically very important for them) their employees’ livelihoods. All they want is for the business to survive, and if they can stay a part of it, all the better.

There are typical scenarios: the absence of forfeiture actions suggests landlords are applying a light touch, foregoing rent collection. This reflects that their tenants are not trading and are unable to pay rent. Also, there are no alternative occupiers/uses for their premises.

There may be revenue liabilities warehoused from before the first lockdown, and trade creditors remaining outstanding. Leasing and loan payments are likely not to have been made. By their absence of enforcement action on foot of these liabilities, SME creditors reflect the uncertainty of recovering their money at this time.

CLRG submissions

A low-cost, reduced process framework for dealing with these latent liabilities is proposed in the October 2020 report of the Company Law Review Group (CLRG), which advocates a Summary Rescue Process (SRP). This has been developed into the ‘Small Company Administrative Rescue Process’ (SCARP), which it is anticipated will be commenced with the enactment of the Companies (Amendment) Act 2021.

At the time of writing, the steps required in the SCARP are:

- The company procures a report from their insolvency practitioner (IP), whose content mirrors the independent expert report in examinership, including the IP’s view that the company has a reasonable prospect of survival, subject to certain matters occurring,

- The company issues a notice of cessation of payments, advising its creditors it is entering an insolvency process,

- Should the stakeholders oppose it (for example, on the grounds that the process is being invoked for improper means), they can appeal the notice of cessation of payments to (it is envisaged) the Circuit Court,

- If protection from enforcement action by creditors is required, there will be a fast-track application to court for protection against sequestration or execution of the liabilities, as currently occurs on the presentation of a petition/statement of facts in examinership,

- The IP has 50 days in which to put together a scheme of arrangement with the company members and its creditors,

- If opposed, the scheme of arrangement is put to the court for its approval.

The SRP therefore omits a number of steps otherwise required in examinership, namely:

- No petition/hearing for the examiner’s appointment – this means the notice for directions and grounding affidavits are not required and, other than the initial report by the IP, there are no costs associated with initiating the process,

- No requirement to report to the court in 35 days from the IP’s appointment, and

- No requirement to file the report on the outcome of the meetings in court pending a hearing on the outcome of creditors’ meetings.

At this time, one useful tool in examinership is omitted from the new scheme – the power to assume executive control of the company. While not often invoked, this power being available can make the difference when the scheme of arrangement is prepared for approval.

A place for SCARP

In the absence of an efficient mechanism to resolve the liabilities incurred by businesses highlighted above, the supports being rolled out by the State in response to the COVID-19 lockdowns are blunt.

Even if a business can access credit or investment, that money will not be best utilised if all it can be used for is to address historic liabilities, and not provide for its future cash-flow requirements.

With this process, there are more prospects of wholesale recovery, albeit that the pain will properly be spread across the economy. As set out above, there are common categories of debt across companies that have felt the impact of the lockdowns – between landlord, Revenue, trade, and finance creditors.

The fundamental test in examinership is that, if a scheme of arrangement provides that a creditor gets less than they would if the company went into liquidation, they are unfairly prejudiced in the scheme, and it cannot be confirmed by the court. It is proposed that the same test will be provided for in the SCARP.

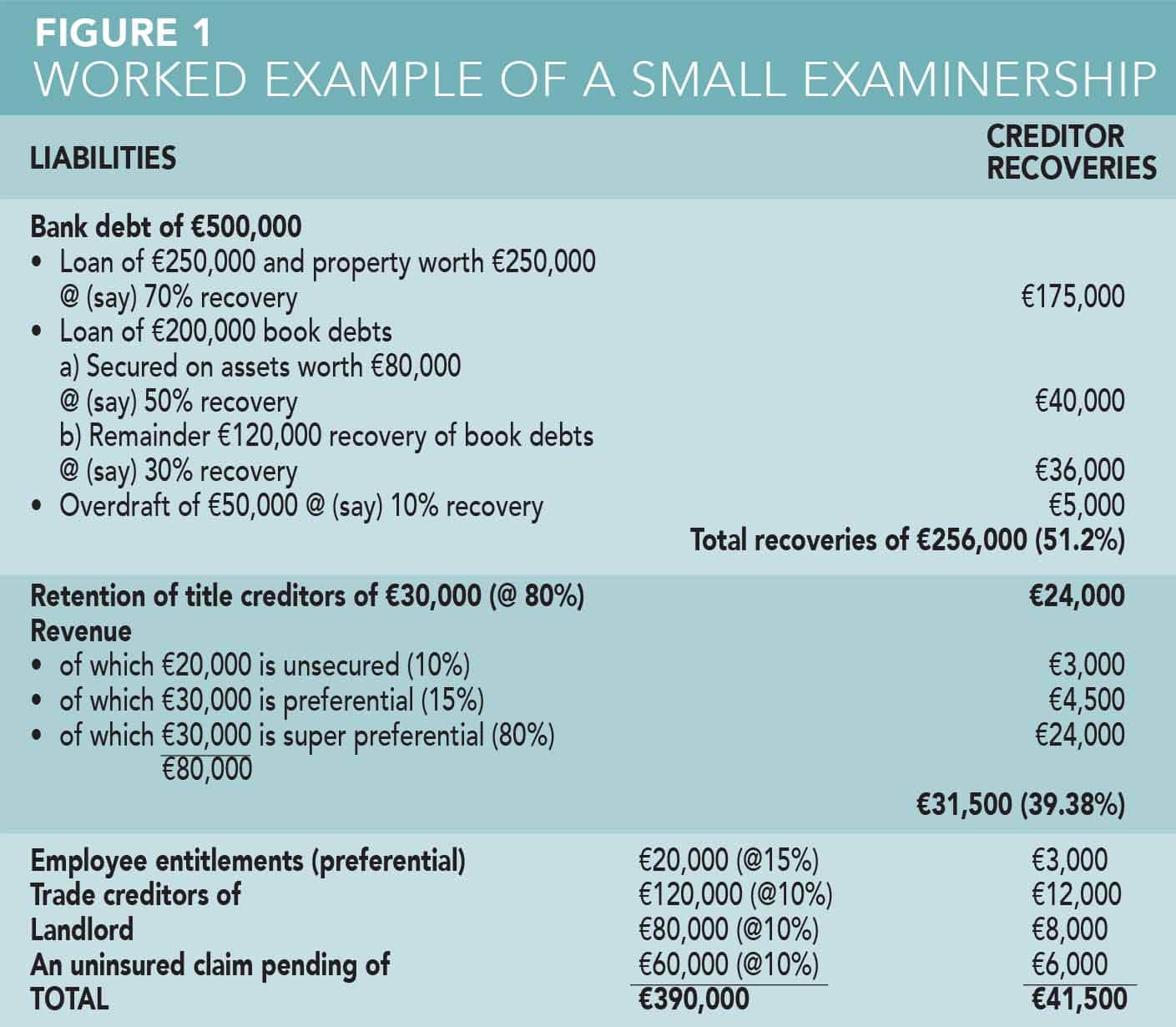

In Figure 1, I give a worked example of a typical examinership case. Here, bank and retention of title creditors accept payment when the business returns to turning over its trade, with the bank rescheduling payments over a longer period.

The bank will rely on personal guarantees (PGs) for any deficit between the sum provided for in the scheme of arrangement, and the amount owed by the company. The guarantor will rely on their income from the company to discharge their obligation on the PG over time.

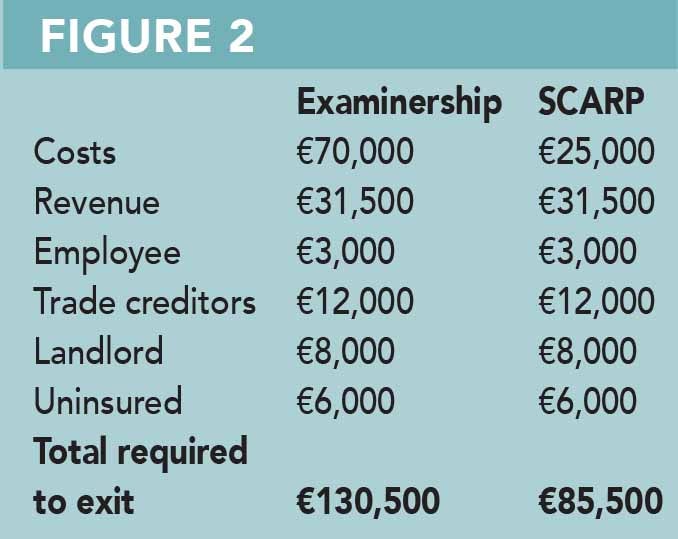

Therefore, the sum required to exit from examinership will be the costs of the examinership, plus the dividends needed to discharge Revenue, employee creditors, trade creditors, and the uninsured claimant (see figure 2).

As can be seen from the comparison between the outcome of a restructure run under examinership versus the SCARP, process costs make a substantial difference in the funds required to exit the restructure, particularly where the amounts involved are relatively small. The reduced costs of the SCARP reflects the exclusion of typically unnecessary steps.

A fourth way

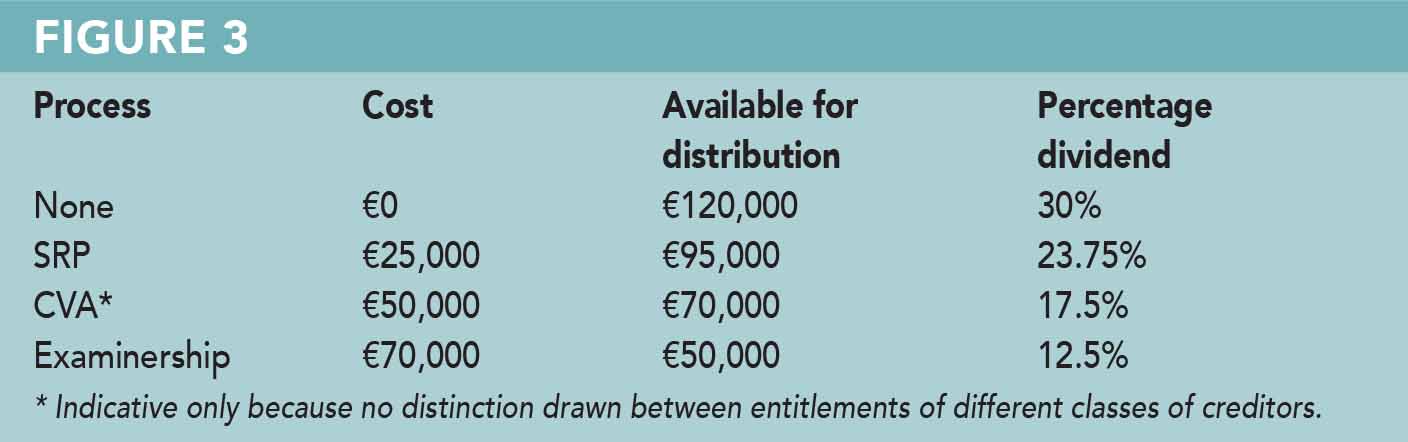

There are currently two restructuring options: a creditors’ voluntary arrangement (CVA) and examinership. Taking the cost of a CVA at €50,000 and examinership as set out above, including SCARP in the mix gives a fourth option – an agreed outcome to the restructure, based on avoiding restructuring costs.

Taking debts of €400,000 and investment of €120,000, these are the funds available to creditors* (see figure 3).

The solicitor’s role

As the first to be told of notifications of legal proceedings in respect of (for example) forfeiture of a lease or an intention to institute legal proceedings to recover a debt, in many situations, the company’s solicitor will be first person outside the boardroom to become apprised of its difficulties.

For the reasons set out above, the SCARP will rebalance the power equation between the creditor and their debtor, particularly in the light of the ‘no blame’ nature of business difficulties arising from the COVID lockdowns.

The CLRG’s scheme provides that the same categories of professionals as are currently able to act as liquidators and examiners (which include solicitors) can act as the SRP process overseer.

The Companies Acts need to provide an efficient, non-judgemental framework for companies to survive and jobs to be saved. The development of the SCARP recommendations, as contained in the proposed bill, accomplish that – and need to be implemented urgently.

Read and print a PDF of this article here.

Barry Lyons is a solicitor specialising in corporate restructuring. He was co-opted to the Company Law Review Group in its review of the examinership process in the expectation of post-COVID business difficulties